Celebrating the Research of Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger & Honoring the Legacy of Caspar René Gregory

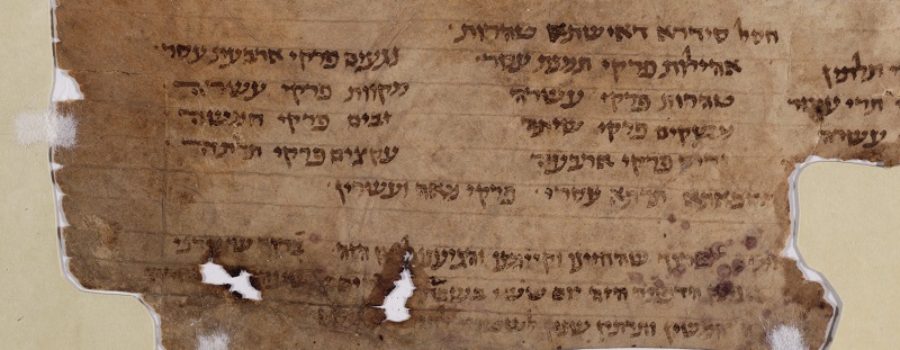

It is with great excitement that I bring to your attention a recent article by Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “The oldest Hebrew manuscript dated by its colophon: a leaf of a Mishna manuscript with Babylonian vocalization in Toronto,” which was published as part of The Cambridge University Library’s Fragment of the Month Series (for June 2023), and is available here (https://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/collections/departments/taylor-schechter-genizah-research-unit/fragment-month/fotm-2023/fragment-4). This article marks a significant milestone in Hebrew manuscript studies. Prof. Olszowy-Schlanger’s groundbreaking research uncovers ‘MS A’, the earliest explicitly dated Mishnah manuscript, shedding new light on early fragments from the Cairo Genizah. After conducting a review of the relevant scholarly discussions, Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger describes how the ‘MS A’ fragment is now known as “MSS Friedberg 9-001 c. 1 and another folio of the same manuscript, MSS Friedberg 9-001 c. 2 [and] have been promptly identified as joins with the other fragments belonging to Friedmann’s and Kahle’s ‘MS A’ by the team of the Friedberg Geniza Project.” Furthermore, her research now conclusively shows that the age of this fragment dates from 840/841 CE, which, “not only makes of ‘MS A’ the earliest dated manuscript of the Mishna, but also the very earliest medieval Hebrew book explicitly dated by scribal colophon.” She describes: “Such an early dating provides a new palaeographical milestone for comparative analysis of other manuscripts and sheds new light on the chronology of the early fragments from the Cairo Genizah.” The implications of this discovery extend beyond the manuscript’s dating, offering a valuable opportunity for comprehensive comparative analysis and a fresh perspective on the fragments from the Cairo Genizah.

Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger’s contributions to the field of medieval Jewish history and manuscript studies have consistently been recognized as groundbreaking. Her extensive research, deep expertise, and meticulous analysis have significantly advanced our understanding of Jewish manuscripts, particularly those from the medieval period. Through her rigorous scholarly work, she has shed new light on various aspects of Jewish culture, language, and textual traditions.

Her extensive research on Hebrew and Hebrew-Latin Documents from Medieval England has shed light on the knowledge and practice of Hebrew grammar among Christian scholars in pre-expulsion England. Notable works in this area include:

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “The Knowledge and Practice of Hebrew Grammar Among Christian Scholars in Pre-Expulsion England: The Evidence of ‘Bilingual’ Hebrew-Latin Manuscripts,” in Nicholas de Lange, ed., Hebrew Scholarship in the Medieval World (Cambridge: CUP, 2001), 107-128, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38307764);

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “With That, You Can Grasp All the Hebrew Language: Hebrew Sources of an Anonymous Hebrew-Latin Grammar from Thirteenth-Century England,” in Nadia Vidro, et al., eds., A Universal Art: Hebrew Grammar across Disciplines and Faiths (Brill: Leiden, 2014), 179-195, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38308275);

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, Hebrew and Hebrew-Latin Documents from Medieval England: A Diplomatic and Palaeographical Study, two volumes (Turnhout: Brepols, 2016).

As well, Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger has made significant contributions to the emerging field of ‘Books within Books’, focusing on new discoveries found in old bookbindings, founding the Books within Books project in 2009. Her research and leadership in this area has revealed fascinating insights, as evidenced in:

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “Binding Accounts: A Ledger of a Jewish Pawnbroker from 14th Century Southern France (MS Krakow, BJ Przyb/163/92),” in Andreas Lehnardt and Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, eds., Books within Books: New Discoveries in Old Book Bindings (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 97-147, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38308253);

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “The European Project ‘Books within Books’ (BwB): Hebrew Manuscripts in Medieval Christian Book Bindings,” in Ursula Schattner-Rieser and Josef M. Oesch, eds., 700 Jahre jüdische Präsenz in Tirol (Innsbruck: Innsbruck University Press, 2018), 49-58;

- Emma Abate and Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “Manuscripta manent: ‘Books within Books’, An Overview,” in Mauro Perani and Emma Abate, eds., Medieval Hebrew Manuscripts Reused as Book-bindings in Italy (Leiden: Brill, 2022), 21-31.

‘MS A’ holds a significant place in the study of medieval Jewish manuscripts. This remarkably early genizah text can be traced back to the medieval yeshivot of Iraq, where it was produced and likely utilized within scholarly circles. Its distinct features of Babylonian vocalization, indicative of its origin, provide valuable insights into the linguistic and textual traditions prevalent in those yeshivot. For further exploration of research on the yeshivot of Iraq during this medieval period and earlier, see Moshe Gil, “The Babylonian Yeshivot and the Maghrib in the Early Middle Ages,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, vol. 57 (1990-1991): 69-120, and for these yeshivot of an earlier era, see Isaiah M. Gafni, “Nestorian Literature as a Source for the History of the Babylonian Yeshivot,” in Jews and Judaism in the Rabbinic Era: Image and Reality – History and Historiography (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019), 269-280.

The fragments of the manuscript analyzed by Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger in “The oldest Hebrew manuscript dated by its colophon: a leaf of a Mishna manuscript with Babylonian vocalization in Toronto,” available here (https://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/collections/departments/taylor-schechter-genizah-research-unit/fragment-month/fotm-2023/fragment-4), are scattered across global locations such as Cambridge, Oxford, St. Petersburg, Jerusalem, New York, and Toronto, represent a range of tractates from the Mishnah. Remarkably devoid of Talmudic or commentarial content, these fragments collectively provide a rich source of information for the study of Hebrew manuscript traditions. For examples of her earlier contributions in related areas, see

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “The Hebrew Bible,” in Richard Marsden and E. Ann Matter, eds., The New Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 2: From 600 to 1450 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 19-40, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38308175);

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “Manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible in the Middle Ages,” in Geoffrey Khan, ed., Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, vol. 2 (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 572-575, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38308212);

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “The Anatomy of Non-Biblical Scrolls from the Cairo Geniza,” in Irina Wandrey, ed., Jewish Manuscript Cultures: New Perspectives (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2017), 49-88, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38308351);

- Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, “User-Production of Hebrew Manuscripts Revisited: The Case of Manuscript Oxford, Bodleian Library, Huntington 200,” in David Durand-Guédy and Jürgen Paul, eds., Personal Manuscripts: Copying, Drafting, Taking Notes (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2023), 335-357;

Undoubtedly, these discoveries in medieval Hebrew manuscripts, especially in paleography and codicology, will stimulate extensive scholarly discussion among renowned researchers around the world. In light of these exciting advancements, I offer the following brief discussion to serve as an addendum of sorts, to further enhance the insights presented in footnote #15.

“Gregory’s Rule,” which refers to the understanding that parchment sheets were arranged in a specific order to maintain the consistency and symmetry of a book, was utilized by Professor Olszowy-Schlanger in her new article, thus allowing her to decipher key aspects of the structure and origins of ‘MS A’, identifying it now as the oldest known dated Mishnah manuscript.

“Gregory’s Rule,” named after the renowned German-American theologian Caspar René Gregory, holds immense significance in the field of codicology, which focuses on the examination of books as physical objects and their historical context. This principle of “Gregory’s Rule,” clearly articulated in his article in Caspar René Gregory, “The Notebooks of Greek Manuscripts,” Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 29 (1885): 261-268, esp. pp. 264-265 (French), provides valuable insights into the physical characteristics of ancient manuscripts, such as the texture and color differentiation between the ‘hair side’ and the ‘flesh side’ of the parchment, the consistent size of sheets, and the arrangement of these sheets. In this aforementioned article from 1885, originally delivered as a lecture in a gathering of The Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Caspar René Gregory detailed this process, explaining that the manuscript is prepared in a specific order to ensure the ‘hair side’ and ‘flesh side’ of the parchment align correctly when folded into a quaternion, that is, a group of four sheets that are folded to make eight pages. (Note: An English translation and study of this article by Caspar René Gregory, “The Notebooks of Greek Manuscripts,” Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 29 (1885): 261-268 (French) is underway, and is slated for future publication. Please contact me if you have any particular research interest in this topic.)

While some may argue that these rules are self-evident and require no further discussion, Caspar René Gregory recounts his own experience of sharing the rule with a highly esteemed paleographer who initially dismissed it. However, it was through painstaking examination of hundreds of manuscripts across different libraries that Gregory gained the confidence to publicly assert the significance of these rules. Indeed, he wrote: “Some people may be tempted to say that the matter is self-evident and there is no need to even discuss it. On the contrary, when the rule first occurred to me, I communicated it to one of the most eminent paleographers of our time, and he utterly refused to admit it. It was only after examining several hundreds of manuscripts in various libraries that I dared to publicly articulate the rule.”

It is important to acknowledge that while “Gregory’s Rule” provides valuable insights into the physical characteristics and arrangement of ancient manuscripts, it is not an all-encompassing rule. There are manuscripts that deviate from its application, as exemplified by Sotheby’s recently sold Codex Sassoon, hailed as ‘The Earliest Most Complete Hebrew Bible’. Alongside other manuscript fragments studied in recent years, these deviations from “Gregory’s Rule” demonstrate the diversity and complexity of manuscript construction, which goes beyond the scope of this post.

Are you curious about the person behind “Gregory’s Rule” after learning about its application by Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger this week? Let’s explore the man behind this theorem.

Caspar René Gregory, for whom “Gregory’s Rule” is named, left an indelible mark on the field of manuscript studies. Two decades ago, a poignant assessment of Gregory’s legacy appeared in Anthony Grafton, “The Precept System: Myth and Reality of a Princeton Institution,” Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 64, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 467-503, where he wrote: “Caspar René Gregory, a product of the Princeton Theological Seminary who became professor of New Testament Greek in Leipzig, wrote works in German that remain standard to this day, and died during World War I, at the age of seventy, fighting on the Western Front as a German infantryman.” For an expanded study on The “Gregory’s Rule” originator, and his experiences as this fallen scholar, see Timothy J. Demy, “For Christ and Kaiser: Caspar Rene Gregory and the First World War,” in Andrew Mein, Nathan MacDonald, and Matthew A Collins, eds., The First World War and the Mobilization of Biblical Scholarship (London: T&T Clark, 2019), 37-48, who observes: “One unusual illustration of the tragedies of the war are the experiences of New Testament textual critic Caspar René Gregory (6 November 1846–9 April 1917), an American-born New Testament scholar who lived most of his life in Germany and, at the age of sixty-seven, enlisted in the German army as the oldest volunteer to do so, dying on the Western Front in 1917. Interestingly, Gregory was not the only New Testament scholar killed in the war. James Hope Moulton (11 October 1863–9 April 1917), a British nonconformist divine and Greek scholar, also died in the war and on the same day. The death on the same day of these well-known figures in New Testament studies illustrates the effect the war had on one discipline that many people assume was largely untouched by the war.” For those interested in commemorating the Hebrew date of this yahrzeit, it will fall on the 17th of Nisan next year, specifically on April 25, 2024.

In conclusion, the groundbreaking discovery of ‘MS A’, the earliest dated Mishnah manuscript, and Prof. Olszowy-Schlanger’s analysis opens new avenues in the understanding of medieval Hebrew manuscripts. Stay tuned for Prof. Olszowy-Schlanger’s future research on this and related fragments. If you are interested in delving deeper into this topic or discussing the implications of this research with key scholars in the field in either small gatherings or in large workshops, please feel free to reach out to me directly.