For more than a hundert un tsvantsik years, the relationship between the modern innovation of Zionism and diverse Jewish communities has undergone intense scrutiny, revealing a spectrum of perspectives on Jewish involvement in reestablishing a Jewish presence in the Land of Israel. The realization of this effort culminated in the pivotal 1947 United Nations vote that recognized the establishment of the State of Israel. (From my own religious standpoint, this milestone carries profound significance and embodies a non-Messianic interpretation of reishit tzemichat geulateinu, which continues with earlier traditions of geulah be-derekh ha-tevah. If you’re interested in learning more about this perspective, please don’t hesitate to reach out!)

As an example of the scrutiny that the relationship between Zionism and religious Jewish communities faced, one can look towards the case of Reform Judaism. During the early twentieth-century, Reform Judaism officially opposed Zionism, offering a prime example of the intricate interaction characterized by ideological engagement and tension. Notably, influential Reform leaders initially displayed considerable support for Zionism before the movement eventually shifted towards neutrality or even pro-Zionism. This early alignment played a role in laying the groundwork for future ideological reconciliation of Zionism within American Reform Judaism. For a sample of some of the scholarship on this topic, see Michael A. Meyer, “American Reform Judaism and Zionism: Early Efforts at Ideological Rapprochement,” Studies in Zionism, vol. 7 (Spring 1983): 49-64, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38354994); Marc Saperstein, “Israel and the Reform Rabbinate,” in Joseph Glaser, ed., Tanu Rabbanan: Our Rabbis Taught – Essays on the Occasion of the Centennial of the Central Conference of American Rabbis (New York: CCAR, 1990), 105-131, available here (https://www.academia.edu/36883863); David Ellenson, “Reform Zionism Today: A Consideration of First Principles,” Journal of Reform Zionism, vol. 2 (March 1995): 13-18, available here (https://www.academia.edu/37665784); Michael A. Meyer, “Toward a Reform Jewish Vision for Zion,” CCAR Journal: A Reform Jewish Quarterly, vol. 54, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 98-112, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38356701); and Michael A. Meyer, “A Zionism of ‘And Nevertheless’,” CCAR Journal: The Reform Jewish Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 2 (Spring 2018): 151-154, available here (https://www.academia.edu/38356934), among much else.

Within the Orthodox community, similar examination of viewpoints can be observed – and in this brief essay, I would like to address a particular episode in the ultra-Orthodox (or Haredi, as their adherents might now describe themselves) and Religious Zionist communities. One century ago, this week, the challenge of bridging an ideological divide between Mizrahi and Agudath Israel factions took center stage – during the inaugural Knessiah Gedolah, also known as the World Congress of the World Agudath Israel, held in Vienna. (Fun fact: the creation of the Knessiah Gedolah by Agudath Israel was modeled after the World Zionist Congress, first convened by Theodor Herzl in 1897.) However, despite dedicated efforts by some leaders from both sides of the aisle of Mizrahi and Agudath Israel, the envisioned unity did not materialize. The year was 1923, a momentous period defined by the wrestling between contrasting ideals within the Orthodox community. At this August gathering, the key players included representatives from the Agudath Israel and Mizrahi factions, who each championed their distinct visions for what Judaism’s response could be for the evolving Zionist movement. The event’s backdrop was marked by the overarching question of unity and ideology: could the ideological chasms that separated these groups be bridged for a common cause? As emissaries from diverse Orthodox backgrounds converged in Vienna, the world watched to see if an alliance could emerge that would reshape the trajectory of Orthodoxy’s engagement with Zionism. While the formal proceedings were intended to pave the way for harmonious collaboration, the outcome revealed the complexities and limits of forging consensus. Despite earnest efforts to find common ground, the ideological rifts within the Orthodox community remained too deep to overcome. The ambitious goal of unification remained elusive, casting a light on the divergent trajectories of Agudath Israel and Mizrahi within the larger context of Jewish response to Zionism. Yet, even amid the disappointments of unrealized unity, the 1923 gathering left an enduring legacy (and see more on this below).

For a concise overview of the intricate relationship among Agudath Israel, Mizrahi, and the World Zionist Organization, see the masterful work by Daniel Mahla, “No Trinity: The Tripartite Relations between Agudat Yisrael, the Mizrahi Movement, and the Zionist Organization,” Journal of Israeli History, vol. 34, no. 2 (July 2015): 117-140; Daniel Mahla, Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion: From Prewar Europe to the State of Israel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), and see Naomi Seidman, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition (Oxford: Littman Library, 2019), and earlier in Yosef Salmon, “Zionism and Anti-Zionism in Traditional Eastern European Jewry,” in Do Not Provoke Providence: Orthodoxy in the Grip of Nationalism (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2014), 161-191; Gershon Bacon, “Imitation, Rejection, Cooperation: Agudat Yisrael and the Zionist Movement in Interwar Poland,” in Zvi Gitelman, ed., The Emergence of Modern Jewish Politics: Bundism and Zionism in Eastern Europe (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), 85-94, available here (https://www.academia.edu/32093081); Gershon Bacon, The Politics of Tradition: Agudat Yisrael in Poland, 1916-1939 (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1996), available here (https://www.academia.edu/39632504); and Aviezer Ravitzky, “Munkacs and Jerusalem: Ultra-Orthodox Opposition to Zionism and Agudaism,” in Shmuel Almog, Jehuda Reinharz, Anita Shapira, eds., Zionism and Religion (Hanover: Brandeis University Press, 1998), 89-67, available here (https://www.academia.edu/36938953), among much other academic research on this topic.

Discussions about this gathering were in the news again, several years ago in 2015, following the publicized discovery of an authentic video footage of The Chafetz Chaim (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=87XlDRjmPME), which I have discussed elsewhere in an article “Rare Footage of the Chofetz Chaim Surfaces—From Fox News(reel),” co-authored with Pini Dunner for Tablet Magazine (https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/chofetz-chaim-footage), though my initial interest into this inaugural Knessiah Gedolah was sparked several years earlier while perusing the 1980 memoir The Path of a Pioneer: The Autobiography of Leo Jung. Rabbi Leo Jung, had arrived the previous year, in 1922, to serve as rabbi at The Jewish Center in Manhattan, and in his memoir, published nearly sixty years later (when he was ‘still’ at The Jewish Center), included a photograph of his attendance at the aforementioned Knessiah Gedolah, where he stood alongside Polish Rabbis and Senators. The photo (included below) is on the same page as the portraits of his parents, Rabbi Meir Zvi Jung and Mrs. Esther (Silberman) Jung. Rabbi Jung’s autobiography offered no contextual details about this photo or his presence at the conclave. This puzzling gap was amplified upon discovering an article—a contemporaneous document that has been entirely overlooked within the scholarly literature—penned by Rabbi Jung himself. Titled “The ‘Knessiah Gedolah’ and the Agudath Israel,” it appeared in The Jewish Forum, vol. 6, no. 7 (October 1923): 506-509 (reprinted in the Appendix below). Subsequently, I began extensive research into the proposed merger between Agudath Israel and the Mizrahi movement, and this ongoing academic research project is being conducted in collaboration with several colleagues.

As Agudath Yisrael’s influence grew, especially post-Vienna convention, Mizrahi navigated the challenge of balancing cooperation with secular Zionism. Vienna’s emphasis on traditional orthodoxy prompted Mizrahi to maintain its religious commitment while engaging Zionism. Mizrahi aimed to integrate religious observance into Zionism, believing a Jewish homeland could blend tradition with modernity. Faced with Agudath Yisrael’s counter-Zionism, Mizrahi positioned itself as a bridge – of spiritual center, as its name connotes – and aspired towards uniting religious and secular Zionism. Advocating unity, it collaborated with secular Zionists while safeguarding religious values.

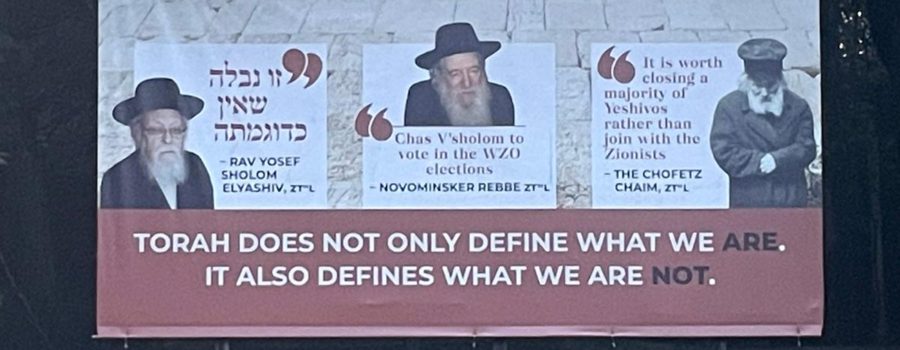

While the battles between those of ideological leanings of the Agudath Israel and Mizrahi have largely receded, periodically, ideological tensions resurface between the ideological camps, and most recently in an article by the esteemed Rosh Yeshiva of the Ner Israel Rabbinical College in Baltimore, Rav Aharon Feldman (and a member of the Agudath Israel’s Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah (Council of Torah Sages), in “Treif Into Kosher: The Story of Eretz Hakodesh,” Dialogue: For Torah Issues & Ideas, no. 9 (Fall 2022): 10-35, a polemic is currently being waged within the Haredi community and that reflects a narrowing divide between the Haredi and Religious Zionist communities (and related to this, see also the photo of a billboard in the Catskill Mountain region that I observed several weeks ago), responding to a Haredi community that has leading rabbinic leaders have provided guidance and stamp of approval at participation in the elections of the World Zionist Organization. At stake are significant financial resources, in a manner reminiscent of the debates of the 1923 Vienna gathering, and the reshifting of the communal dynamics in this area is something that is well-worth to be watching.

Much like the efforts that existed within the Reform Movement at the time, in the context of a conciliation between the Agudath Israel and Mizrahi in 1923, their common conversations were marked by a delicate attempt to find common ground despite their differing approaches to Zionism. The Agudath Israel’s anti-Zionist stance and emphasis on traditional Orthodoxy posed a challenge to any potential collaboration with the Religious Zionist orientation of Mizrahi. However, both movements recognized the need for unity within the Orthodox Jewish community, particularly in response to the then-growing influence of secular Zionism. Now, a century later, many of these organizational terms and descriptions have evolved meanings and have impacted the current political maneuverings within the State of Israel – but that, of course, is a conversation for another day.

Although the desired religious unity between the Agudath Yisrael and Mizrahi movement was not achieved, an unexpected outcome arose from that first gathering of the Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna – the establishment of Rav Meir Shapiro’s Daf Yomi program, a daily Talmudic study under Agudath Israel’s banner. The history of this movement was described in February 2020 lecture by Professor Sid Z. Leiman, “The Daf Yomi Phenomenon: Image and Reality,” which was hosted by the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at Harvard Law School. See also Sidney B. Hoenig, “The Daily Study Task: The Daf Yomi,” The Orthodox Union, vol. 7, no. 4 (February 1940): 4; Max Oelbaum, “Letter: Rabbi Meir Shapiro Was Not Originator of the Daf Yomi,” The Jewish Press (4 July 1967): 39; “Daf Yomi Starts Anew With an ArtScroll Difference,” The Jewish Press (28 December 1990): 18; A. Yosefsohn, “The Daf Yomi and its History: This is How it all Began,” The Yated Neeman, vol. 9, no. 38 (1 October 1997): 15; Elazar Katzman, “Sparks of Ohr ha-Meir: Unknown Chapters in the History of the Daf Yomi,” in Shlomo Gottesman, ed., Ha-Meir la-Olam (Brooklyn: Daf Yomi Commission of Agudath Israel of America, 2005), 363-423 (Hebrew); Marc B. Shapiro, “Talmud Study in the Modern Era: From Wissenschaft and Brisk to Daf Yomi,” in Sharon Liberman Mintz and Gabriel M. Goldstein, eds., Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein (New York: Yeshiva University Museum, 2005), 103-110; Yehoshua Baumel, “Daf haYomi: The Daily Leaf,” in Rav Meir Shapiro: A Blaze in the Darkening Gloom, fourth edition (Jerusalem: Feldheim, 2012), 161-172, among other writings.

Subsequent years brought the devastating decimation of European Jewry during the Holocaust, followed closely by the establishment of the State of Israel. This context, unforeseen during the Vienna gathering, now shapes all discussions about Zionism. To ignore the impact of these episodes in is to overlook the historical realities on the ground, and makes for understanding the contemporary realities that much more difficult.

Appendix:

By Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung

(An Interview with the Editor)

The “Knessiah Gedolah” and the Agudath Israel

The Jewish Forum, vol. 6, no. 7 (October 1923): 506-509

My object in visiting Dr. Leo Jung was to get first hand information on the World Congress of orthodox Jews at Vienna, to which he was a delegate. The interview here presented, we believe, will prove of interest to all parties in Israel.

In a secluded study in the great “Jewish Center” building on West 86th Street, I met him a few days after his arrival from Europe, where he had spent his summer’s vacation.

Dr. Jung seemed full of fresh vigor for what he considers his life work: “the assertion also in this country of virile systematic Orthodoxy, the combination of Torah and Derech Eretz (good manners), of which the Center is a symbol and its school a high effort to produce that type.”

“Did the Knessiah Gedolah justify its name?” was my first question.

The Knessiah Gedolah (The Great Assembly) was truly representative of Jewry. Among those who participated were business men and university professors, leading industrialists, 506 thinkers and men of affairs, the capitalist and the workingman, the rich and the poor, the “Talmid Chacham” (scholar) and the “am-Haaretz” (the man in the street). What united them was the ideal, their standard of life and faith. If the Knessiah had done no more than reunite the masses of Jewry under the banner of the Torah, making Torah the one platform from which shall issue. Jewish efforts, it would have achieved historic dignity, creating a turning point in modern Jewish history.

Actually, it did much more.

Apart from Western Europe, the Orthodox Jew was known for the combination of idealism and “batlanuth” (technical inefficiency). He was regarded as a “Luftmensch,” with his head in heaven and his feet not quite reaching the ground. He was individualistic, in that he was capable by the inspiration of his own “Kavanah” (devotion) to raise himself to a very high degree of ethical perfection, to be kind to the stranger, upright and reasonable towards all, to follow his ideal through thick and thin, unperturbed by the clamor of the mob; to pour this inspiration into his children and make them continue where he had to stop, with the same fervor and superhuman endurance. As individualists the orthodox reach tremendous heights. But as a mass they were disorganized. When pogroms overtook our people they would give away the last shirt. He would support with even love the Yeshibah in his city, and the struggling colony in Palestine; with even zeal he would work for the emancipation of the Jew in Morocco and for the improvement of the Jewish social status in his country; but his sense of system was defective. He was inefficient and this was especially manifest in political life. He did not care for politics. They took him away from his Torah. They had too little idealism and too much self-seeking; for his taste. He, therefore, allowed the secessionist to wrest political influence from him.

“Who constituted the Knessiah Gedolah?” I inquired. Here Rabbi Jung became enthusiastic:

They all aimed at saving the Jew for Judaism and Judaism for the Jew. The “Knessiah” was the outward expression of the inward conviction that as far as Judaism was concerned, “East is not East and West is not West,” but both are servants of God, children of Israel and charged with one and the same task of the Kingdom of priests who are to preach God through the Godliness of their life.

I said it was the outward symbol of an inward harmony. Yet even in its outward appearance it was something unique, for it represented the reunion of organized “k’lal Yisrael.”

“Does the ‘Agudath Israel’ bear in mind the need for unity in Israel?” I bluntly questioned.

It represents the unity of loyal Israel.

For the first time since our national independence was destroyed did we find a Congress like this, led by our greatest rabbis as the head and soul, and by most efficient. laymen as the executive organs of Faithful Israel, endorsed alike by the old generation of the Beth Hamidrash and by the young of the office and the workshop-a forum, on which there appeared the “Chafetz Chayim,” the greatest living gaon, the venerated rabbi of Gura Calvaria, the Professor of Art in Vienna University, the leader of the orthodox labor party, delegates of many thousands of organized orthodox youth, the capitalist and the proletarian. Among them also were numbered such men as Chaim Ozer Grodzinsky, the Rabbi of Vilna, Rabbi M. M. Epstein of Slobodka, the Grand Rabbis of-Radzin and of Chortkov. Chief Rabbi Senator Zirelson of Kishinev, Dr. Hildesheimer, Commercial Councillor S. Bondi, Leo Wreschner of Frankfurt-am Main, Heinrich Eisenmann of Rome, J. Hollander of Copenhagen, Professor Eisler of the University of Vienna, Dr. Breuer, famous lawyer, thinker and journalist of Frankfort, a well-known South American communal worker, a Bagdad nobleman, Senators Mendelsohn and Deutscher of Warsaw, W. Schiff (London), Bloch (Strassbourg), Chief Rabbi Cohen of Cairo, and half a dozen members of Parliament in the various countries of Europe. We must not forget Jacob Rosenheim, the fiery prophet of the Agudah and its philosopher; nor the Rabbi Shapira of Sanok, M.P., the famous defender of his people against the wiles of Polish anti-Semitism; Mr. Guggenheim of Basel, equally known for his munificence and his Jewishness, Mr. Kirshbaum, the head of the orthodox club in the Polish Parliament; Chief Rabbi Katz of Nitra, Rabbi Dr. Levinstein of Zurich, etc.

In their co-operation these Jews realized the great truth which we have been preaching all through the lightless nights of our history, that whether small or great, rich or poor, wise or ignorant, men or women, young or old, we all have one irreducible minimum – our duty toward God; and one all-accessible maximum – our co-operation in His plan to lead the world to the foot of Mt. Sinai, through a life that would preach God by its purity, its kindness and its moral strength.

The Knessiah was fully conscious of its responsibilities and, representing faithful “k’lal Yisrael,” it sent out a message of peace to all Israel, inviting every Jew who feared God and obeyed His commandments, to join its ranks and assist in the realization of its aim, “to solve every Jewish problem in the spirit of the Torah.”

One of the practical steps taken toward this end, was the appointment of a delegation charged with the task of going to Palestine to adjust the differences between Rabbi Sonenfeld and Rabbi Kook.

Another endeavor in this direction was the agreement made with representatives of -the American Agudath Harabanim, according to which articles on debatable points should be free from personal bias, and objective in their treatment of the problems of the Mizrachi and the Agudah.

“What are the solid results of the ‘Knessiah’?” was my next query.

The centralization of all educational efforts in the Goluth: The systematization of Jewish schooling from Cheder to Club, from Yeshivah to Girls’ Academies. Agudath Israel is the organization which everywhere and at all times insists upon the Torah as the guide and the supreme authority in Jewish life. It endeavors to educate the broad masses, young and old, to an appreciation of this simple fact. Another definite result was the centralization of all Palestinian work. In the past the Agudah has had several ventures in Palestine, agricultural and industrial. These are going to be extended and improved. The main purpose of the Agudah is to do constructive work.

“What, in general,” I ventured, “has the ‘Agudath Israel’ accomplished?”

There always was a very large amount of Torah-loyal feeling, masses of great potentialities, but. all disorganized 1 or not employed in a manner likely to produce definite and enduring results. Hence orthodox Jewry all over Eastern Europe, whilst great in strength, was no force to be reckoned with. West European Orthodoxy again had succeeded in creating a type of its own, representing a perfect harmony between Judaism and what good there is in modern civilization. The lion of society, the leading scholar, banker, artist, journalist, who in letter and in spirit was a truly orthodox Jew, there was a natural phenomenon. But West European Jewry which sub-consciously had assimilated too much of the “Weltanschauung” of their neighbors was in danger of becoming devitalized. The study of the Torah did not keep pace with their study of modern culture, and there lurked the possibility of the orthodox “am-haaretz” as typical Western Jew. The Agudath Israel has the undying merit of having merged East and West into a new unity, forging out of two different entities a new one which bears the distinguishing mark of both and has succeeded in eliminating their defects. Agudath Israel has introduced learning and devotion into the West, order and efficiency into the East.

Eastern Europe has sent its rabbis, its “illuyim” (prodigies) and “bachurim” (students)-its “chassidim” into Germany, Austria, Belgium, England. They have kindled there anew, a love for study, together with ‘l devotion, a piety, a heartfulness reminiscent of the school of the Baal Shem Tov. Central European Jewry sent its expert pedagogues 1 its organizers, its psychological and philosophical lights into the East and they helped the East to understand its own soul and to take care of its own treasures.

These notes will help to indicate the work the Agudath Israel has been doing since its inception in 1912, in accordance with the famous saying, “It has re-established the world on Torah and Avodah (service).” Nor was “gmilluth chasadim” (charity) missing. There is a noble list of its work commencing with prisoners of war relief extended from Siberia to England, excellent work in conjunction with immigration into Palestine, a very successful Ukrainian relief fund, social work in Central Europe, and finally, splendidly equipped model orphanages in Eastern and Central Europe.

“What about co-operation with the Zionist Movement?

“In politics we have no immediate interest. In technical matters we would gladly co-operate with every organization. What prevents us from joining in every effort is the fact that since we acknowledge Torah as the supreme arbiter in all Jewish problems, we can never ‘allow Jewish Law to become dependent on the vote of majorities. I would say, in such respects, “Let us march apart and strike together.” Every true Zionist ought to enjoy the work of the Agudah and to wish it every success; for, as a Zionist, he is in favor of the upbuilding of Palestine, and he surely won’t mind that this new Palestine, at least as far as Agudah builds it, will be truly Jewish in its background, its associations and its ultimate aims. I am not a Zionist but I am for Palestine, for a Jewish Eretz Yisrael, with all my heart. For an orthodox Jew it is self-evident-that the restoration of the Holy Land must occupy a very large part of our attention, and our work. But to me, more fearful than the Goluth of Jewry is the Goluth of the Torah-hence all the “difficulties.” The members of my Center have made their contributions toward the Agudah colonies of Palestine in addition to their gifts through other channels towards the upbuilding of Palestine.

“What is the ‘Agudah’ attitude towards the Mizrachi?”

The Agudath Yisrael as such invites every individual Mizrachist to join its ranks. And it is obvious to every thinking Jew- that the Mizrachi in its struggles against the Zionist majority can wish for no better support of their organization than is given by the existence of a great independent orthodox world organization. Personally, I am convinced that we shall not for long remain apart. We are both positive, centripetal forces and I should count the day on which the Mizrachi will join the Agudah, one of the most auspicious not only in the life of those who stillstand aloof, but in the life of all Israel.

The inspiration of the Knessiah has surely touched a responsive chord in the heart of every loyal Jew. Let us hope that all these chords will soon sound together. It will be then like the call of the Shofar, which assembles the masses of Israel above all differences and minutiae, into one united force for God and Torah. Then the aim of Agudath Israel will have been achieved.